Rob Pinney/Getty Images

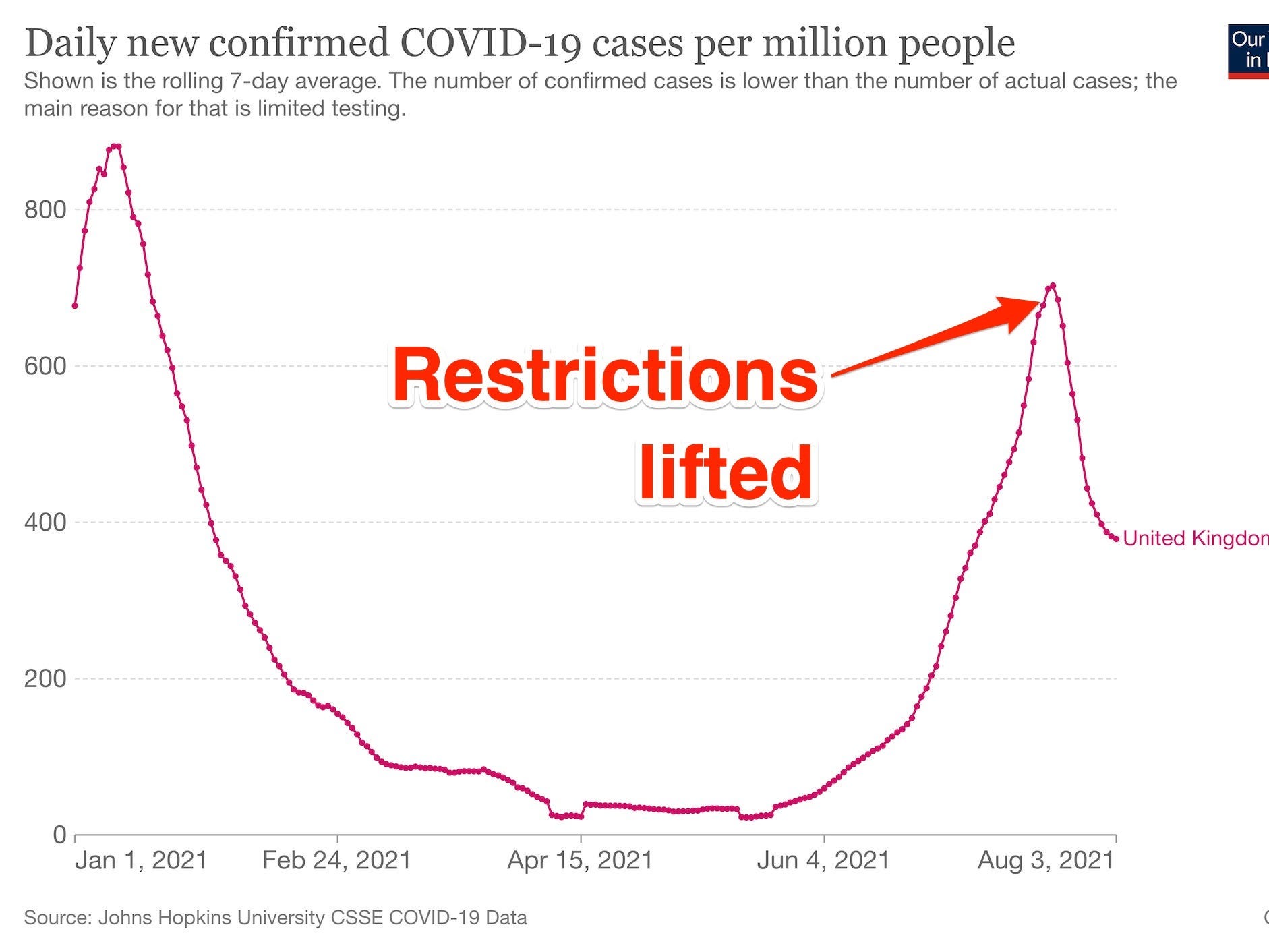

- Almost all restrictions were lifted in England on July 19. A large drop in COVID-19 cases followed.

- Experts suggest that warm weather, school closures, and the end of Euro 2020 might explain the drop.

- But as students return to school and cold weather hits, cases might rise again, say experts.

- See more stories on Insider's business page.

When the UK's Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced that he would be lifting almost all remaining restrictions in England on July 19 even as COVID-19 cases continued to rise in the country, he drew some fierce criticism.

"We must reconcile ourselves, sadly, to more deaths from COVID," Boris Johnson warned. The others nations of the UK – which have separate public-health regimes – took pointedly slower schedules.

But at about the same time as England's unlocking, new daily cases started to plummet. It was the opposite of what many experts expected.

"This is a remarkably rapid decline and one that few anticipated," said Martin McKee, professor of European Public Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, told Bloomberg.

"Overall, it is a bit of a mystery."

Our World in Data; Insider

Soccer might have played a role in the spike

Although it is "really difficult" to know what drove the sharp rise in cases, "there does seem to have been a spike associated with the Euros," McKee told Insider on Tuesday.

The England soccer team went all the way to the finals in the much-awaited championship. From June 11 to July 11, large crowds of supporters celebrated their teams in stadiums and pubs, a breeding ground for infections, prompting WHO experts to express concern.

The end of the championship allowed cases to fall, McKee said.

Wiktor Szymanowicz/Barcroft Media/Getty Images

Summer, warm weather, and individual nerves about unlocking likely contributed to the rapid fall

The effects of lifting the restrictions might also not have been felt yet. A heatwave his the UK in July. The consequence is that there were likely fewer people drinking indoors, McKee said.

People also seem uncertain about going back to pre-pandemic habits.

In a survey on 3,784 adults from the UK's Office for National Statistics (ONS), 60% said they would continue to avoid crowded places.

School closures for the holidays likely also helped bring down cases, McKee said. "It seems likely that schools played a much greater role in transmission than some people were willing to accept."

Has herd immunity been reached? Unlikely

Some experts posit that the UK might have reached herd immunity, which is when enough people have immunity against infection that the virus is incapable of spreading.

Almost 60% of the UK's population have been fully vaccinated, and many have developed immunity from being infected.

"You can run some very simple models to see if the case numbers that we saw earlier this month are consistent with effective herd immunity," Prof Mark Woolhouse of Edinburgh University, told the Observer.

"There are some big caveats but the bottom line is that those figures are consistent with the impact of herd immunity," he said.

McKee thinks that this is "unlikely." Cases are still rising in Israel, where vaccination levels are even higher, he noted.

Also vaccinated people can be reinfected, although at a substantially reduced risk of severe disease, per McKee.

Ian Forsyth/Getty Image

Some experts aren't yet convinced

Professor Tim Spector, from King's College London, expressed suspicion about how representative the figures are.

"The drop is much faster than we've ever seen in previous waves," he told the BBC. "Even after full national lockdowns, leaving the accuracy of the official tally in doubt."

Spector leads the Zoe COVID study, which tracks symptoms for 4 million people globally. Although there has been a drop in cases among the study participants in the UK, it is not as sharp as in the government stats.

Experts worry that problems will surface again in the fall, as children come back to school and the UK winter weather forces people indoors again.

But all in all, it is very difficult to know at this point what the future holds for the UK.

"At this point, I think it's really hard to understand what has happened and what is going to happen in the long term," John Edmunds, a professor of epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, told the Observer.